Cognition

The Metacognitive Framework

This entry will be a bit more personalized and in depth than the rest. It discusses how I currently view psychological and philosophical levels of development. This structure, while borrowing some elements from Integral Theory, is my own, and has been refined over several years.

Introduction

You, as an individual, are never a static role. You grow and change over time and different priorities take precedence in different circumstances. To reflect this in the Metacogntiive Framework, envision yourself as a snake, weaving through different ways of thinking as you encounter new experiences, insights, and struggles. Your “length” as a snake—the number of ranks you actively occupy at a given time—depends entirely on what you’ve lived through, what you’ve learned, and how you’ve chosen to respond.

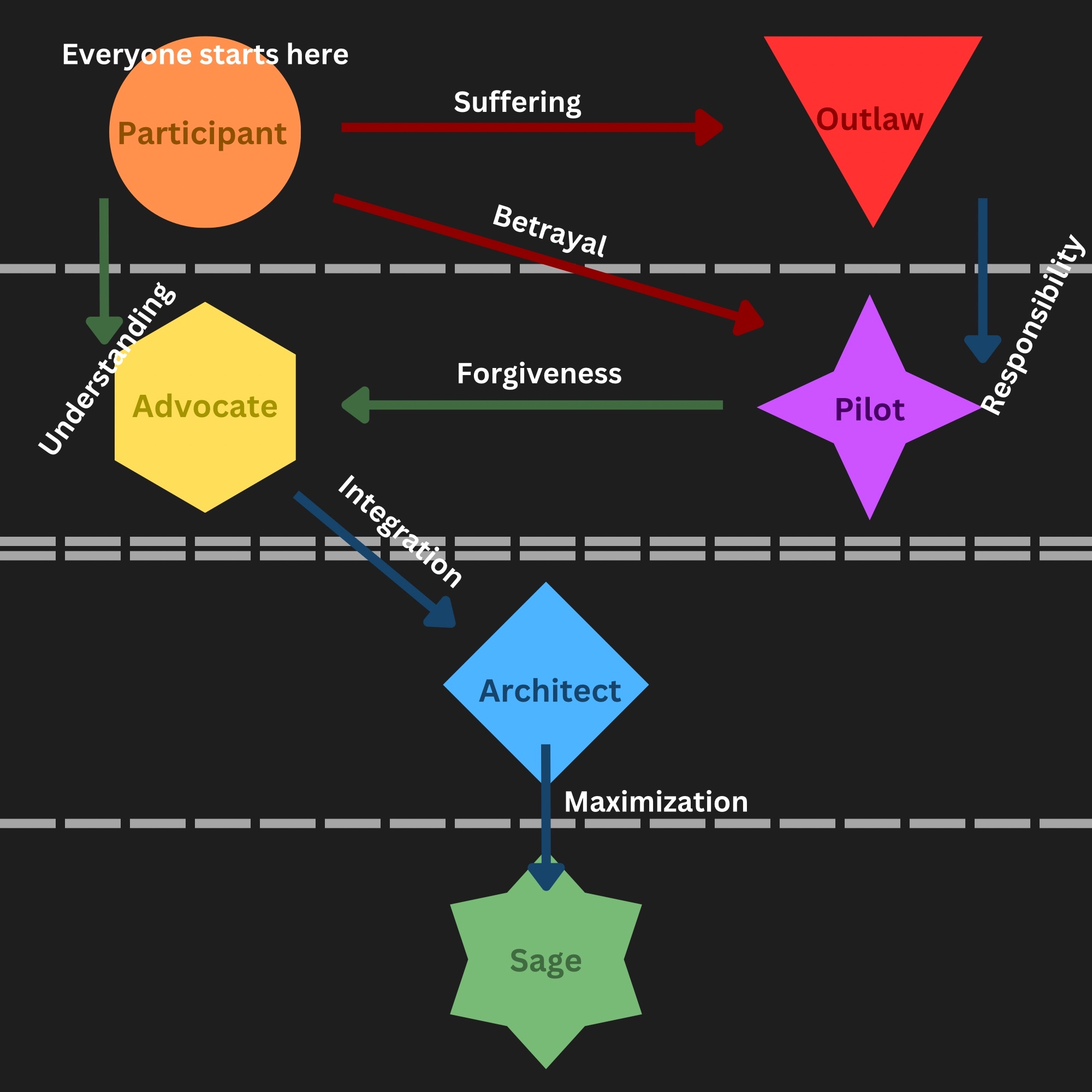

See the Metacognitive Framework below.

And yet, there is one exception: the very first rank. Every person begins life as a Participant, and many never leave this state at all. It is the one fixed point of the framework, the baseline of human cognition, the starting shape from which all others emerge. If you’re curious on why this is: the vast majority of cultures I am aware of raise their children to play by the rules and accept the things told to them by their authority figures. Whether or not they actually do so is not the point, the idea is that everyone starts here because everyone is fed similar messages while they are a child. There are of course exceptions, but this is the most accurate generalization I could make.

This is very important to keep in mind as you read about the framework: unless you are the Participant exception, you almost never occupy a single rank in the framework, but instead occupy several simultaneously. People are complex, and unfortunatly it is impossible to accurately place them in neat and tidy boxes.

Beyond that, the Metacognitive Framework divides life into four tiers of cognition:

- Passive Living: where life is endured more than directed. Includes Participant and Outlaw.

- Active Living: where life is taken into one’s hands, though still through narrow or incomplete lenses. Includes Advocate and Pilot.

- Systematic Living: where multiple valid perspectives merge into structured synthesis. Includes Architect.

- Maximal Living: where life is lived as fully as possible, transcending ego and embracing wisdom. Includes Sage.

Movement between these tiers depends on certain experiences and necessary reconciliations. The framework shows three paths of transformation:

- Red (Pain-based): growth forced by suffering or betrayal.

- Green (Virtue-based): growth through empathy, forgiveness, and understanding.

- Blue (Wisdom-based): growth through knowledge, responsibility, integration, and maximization.

I will walk through these tiers step by step, exploring the ranks, transitions, and lessons of each.

Tier I: Passive Living

Passive living is where human cognition begins. At this stage, people are not yet fully responsible for themselves. They tend to react to life rather than direct it, letting external systems or circumstances shape who they are. Individuals are defined more by their relationship to external forces, whether cooperative or antagonistic, than by inner autonomy.

Participant

Parcitipants believe that their method of living is the one true way. They accept anyone who agrees with them and push away those who don’t.

Everyone starts as a Participant. Participants are not necessarily stupid, but they are oriented toward selflessness without agency. Their lives are framed by the systems around them: family, school, religion, culture, work. They follow the rules, fit into established structures, and play the roles assigned to them. Their sense of value comes from being “good” members of the group: responsible children, loyal employees, supportive citizens, or dutiful friends.

At this stage, meaning is not internally generated. It is borrowed from the external order: from traditions, expectations, and collective identities. Participants rarely ask about the systems they are in, and instead focus on playing their part within it. Their lives are guided by trust in authority and comfort in belonging.

Most of humanity remains here indefinitely. This is not because Participants lack potential, but because the rewards are tangible and stabilizing. Belonging offers safety. Routine offers predictability. Playing one’s given role avoids the existential burden of self-definition. The world is chaotic, but systems make it navigable, so long as one accepts the rules. Participants keep society running, forming its foundation. They are the vast majority, the scaffolding upon which every higher rank stands.

It should be noted that Participants largely believe in inherited worldviews. This is important to consider because not all Participants will be given the same worldviews. As a result, most Participants disagree with each other, since they are trying to play their part in different percieved systems. This creates a strong “us versus them” mentality in the vast majority of Participants, which should sound familiar from either your personal experiences or understanding of the world. Most people are genuinely trying to do what they believe is right without first questioning if others agree with them.

Additionally, passivity has limits. While Participants contribute, they rarely create. Their agency is outsourced to institutions: parents, bosses, laws, traditions. Their sense of “goodness” depends on recognition from others. If that recognition is withdrawn, or if the system itself betrays them, their identity collapses. That fragility is the mark of Tier I cognition.

And yet, some Participants move forward. This happens in three distinct ways:

Through Suffering: Long-term dissatisfaction with passivity can slowly rot the Participant’s trust in society. If they feel unappreciated, stagnant, or exploited, bitterness builds. They begin to see the system as suffocating. In time, this resentment boils into rebellion, pulling them into the Outlaw rank. This is, unfortunately, the most common escape.

Through Betrayal: A sharp, unexpected trauma can break the illusion of security in an instant. A trusted authority fails them, a system they relied on collapses, or a loved one abandons them. The result is a radical disillusionment that fundamentally rewires how they see the world. Instead of belonging, they demand autonomy. This leap sends them directly into the Pilot rank. Though rare, it is among the most dramatic transitions in the framework.

Through Understanding: Some Participants, especially those with nurturing upbringings or reflective temperaments, grow in empathy rather than bitterness. They see not only their role within the system but the struggles of others within it. Instead of rebelling, they seek to champion and uplift those around them. This path leads them into the Advocate rank.

Thus, the Participant stage is the greatest threshold. It is where human cognition begins: safe, social, and structured, but fragile. The Participant clings to belonging until life, through pain, betrayal, or understanding pushes them beyond it.

Outlaw

Outlaws want to control as much as possible. They have a me-first mentality in most circumstances, neglect individual responsibility, and believe they are the exception to the rules.

Outlaws are selfish and passive. They do not take responsibility for themselves, but instead turn outward, trying to control external circumstances and manipulate the environment to bend life to their will.

Outlaws are often misunderstood as rebels or free spirits. They appear to reject the rules, but their rejection is not grounded in wisdom, it is grounded in bitterness. They have discovered that simply “playing along” does not bring fulfillment, yet they are not ready to take true agency. Instead of taking responsibilty for themselves, they lash outward, blaming, scheming, or demanding control over everything but themselves.

The Outlaw represents the only possible regression of thought in this model that is framed as forward motion. They are not actively building a new life, only reacting against the one they feel has failed them. Outlaws may gain short-term satisfaction from breaking rules, seizing power, or manipulating situations, but their way of life is ultimately less sustainable than the path they left it for. Their rebellion is still anchored in dependence. They define themselves against the very structures they claim to reject.

It goes without saying that Outlaws cannot productively participate within society. They are problematic in every sense except with it benefits them. They are the only rank in this framework that almost exclusively harm society.

The only way out of Outlaw is through taking Responsibility of their own lives. They must stop demanding control over what is outside themselves and instead begin to manage what is within. Through knowledge and responsibility, the Outlaw can finally step into the Pilot rank, where selfishness becomes active rather than passive, and agency begins. Unfortunately, the Outlaw must come to this realization on their own due to their reluctance to listen to others. They must fail enough to realize that their way of life is still inadequate.

Tier II: Active Living

In the second tier, people take a more active role in their lives. They are no longer purely passive members of society, but instead seize responsibility or empathy in new ways. Here, selfishness and selflessness remain divided: each rank leans heavily toward one or the other.

Pilot

Pilots believe it’s all up to you so long as you play by the rules. People are different and complex, and as long as you achieve personal success without breaking the rules in the process, then who are they to tell you how to live?

The Pilot represents selfishness turned active. Unlike Outlaws, Pilots take control of their own lives. They are determined, knowledgeable, and unafraid to prioritize themselves. Where the Outlaw seeks control over others and external conditions, the Pilot focuses inward: mastering their own choices, skills, and opportunities. This shift harnesses their selfishness into direct agency rather than reactive struggle.

Pilots are highly pragmatic thinkers. They approach life as a problem to be solved, constantly looking for ways to improve their position and secure their independence. This often makes them innovators, strivers, or lone wolves within a group. Unlike Participants, who find security in rules, Pilots use rules strategically: cooperating when it benefits them, but refusing to be confined by others. They view society as a tool to utilize rather than a structure they must belong to. They view themselves as an exception to the rules, which unlike Outlaws, this causes them distress. They are smart enough to see that they have a higher understanding than those around them (Tier I thinkers) but not yet wise enough to use their knowledge to make themselves happier, only more successful. They believe that one day, they will have full control of themselves.

Additionally, though they know they have more agency than most, and though they sense their limitations, they may refuse to admit them, largely because it hurts their agency and/or ego. This arrogance is a double edged sword. On one hand, it fuels their ambition and gives them courage to take risks others shy away from. On the other, it can blind them to collaboration, leaving them isolated and blinded by their own vision. Still, their sheer determination makes them powerful navigators of life: capable of building careers, forging independence, and escaping cycles that trap others.

There are two paths into this rank:

From Outlaw: This is the more common route. An Outlaw eventually realizes that external manipulation cannot create lasting control. Through self awareness and taking responsibility, they stop trying to bend the world around them and instead begin reshaping themselves. The Outlaw’s bitterness transforms into the Pilot’s discipline: the recognition that the only way forward is through individual responsibility.

From Participant: This is a rare but transformative leap. Normally, Participants live comfortably within the rules, trusting that if they play their part, life will reward them. But a single devastating betrayal, such as a profound personal loss, a broken trust, or a collapse of their social foundation can shatter this illusion in an instant.

Unlike the slow burn of suffering that leads to Outlaw, betrayal cuts sharply and leaves no room for gradual adjustment. It forces the Participant to abandon passivity entirely. In this moment, the individual recognizes that blind trust in systems or others can be dangerous, and that their survival depends on prioritizing themselves. Instead of becoming bitter and manipulative like the Outlaw, they leap straight into assertion: choosing to seize control of their own life with urgency. This unexpected awakening bypasses rebellion and lands them in the Pilot’s mindset: self-reliant, determined, and unwilling to be caught vulnerable again.

Because this transition is so abrupt, it can create Pilots who are sharper, more focused, and more driven than those who arrived from Outlaw. But it also carries scars: these Pilots may carry deep suspicion toward others, a lingering distrust born from betrayal, and a tendency to overcorrect by hardening themselves too much.

The only path forward from Pilot is through Forgiveness. Pilots must learn to forgive: not specifically those who hurt them, but in general. Forgiveness here is less about radical compassion and more about perspective, recognizing that most people act from limited understanding, not malice. Without this, Pilots remain self-absorbed and defensive, stuck in a cycle of relentless self-prioritization. With forgiveness, however, they soften, broaden, and begin to open themselves to the inner lives of others. This act of grace allows them to grow into the Advocate rank, where selflessness becomes active.

Advocate

Advocates want to include and support everyone except those who disagree. They view the world as better than it truly is and, although noble, often do more damage than good because of it.

The Advocate is selfless and active. They fight for others, empathize deeply, and take on the role of hero, leader, or protector. Unlike Participants, they do not merely follow the rules, but also champion others’ needs. Their identity is built around service, sacrifice, and empathy, often at the expense of themselves.

Advocates are driven by a moral compulsion to help. They cannot stand by when someone is suffering, and they often feel personally responsible for lifting others up. This gives them a deep sense of purpose, but it also comes with a heavy emotional cost. Advocates frequently live with a paradoxical mix of fulfillment and exhaustion: they feel meaningful in their service, yet drained by the constant outpouring of energy.

Their empathy extends far. Unlike Pilots, who see the world primarily through their own perspective, Advocates deliberately adopt the perspectives of others. They listen, validate, and recognize multiple viewpoints. But this gift can easily become a weakness. Too much validation risks undermining growth, not only their own, but also the growth of those they try to help. They may soothe when challenge is needed, excuse when accountability is required, or protect when letting someone fail would teach them more. In a sense, they are too noble. Read The Fallacy of Equality in the Interpersonal Tensions section for more details.

This makes the Advocate the most tragic rank in the framework, not out of malice, but out of misguided virtue. In their relentless pursuit of supporting others, they may reinforce passivity in those still at Tier I, giving Participants reasons to remain dependent or giving Outlaws justification for their bitterness. Advocates may unintentionally become enablers, mistaking compassion for progress.

The only way forward is through Integration: the ability to take multiple perspectives and forge them into structured systems. Advocates must stop holding truths as independent fragments and instead learn to combine them into coherent frameworks. It is not enough to empathize, they must also synthesize. Through integration, Advocates evolve into Architects, transcending the cycle of self-sacrifice and instead building durable systems that empower everyone involved.

Tier III: Systematic Living

The third tier is fundamentally different and much more difficult to break into, hence the double line. Here, cognition is no longer about passivity or activity, but about designing around them. Individuals begin constructing systems that combine multiple valid perspectives together to create the best possible generalized solution. If you’re curious, the Codex is fundamentally rooted in this level.

Architect

Architects want to put everything in its proper place. They are aware of the endless complexities of life and are determined to develop harmony through systemization, not enforcement, contrary to all previous ranks.

The Architect is both selfish and selfless. They do not merely understand or forgive, but instead integrate opposing forces into coherent frameworks. Where Pilots act and Advocates empathize, Architects design.

This shift marks a profound change in mindset. Architects no longer see the world as a set of binaries to choose between: self versus others, rules versus freedom, empathy versus control. Instead, they recognize that all of these opposites can be woven into a system where each side strengthens the other. Their cognition becomes consolidated rather than reactive. At this level, things get a little difficult to explain, but I will try my best.

Architects ask, in general: How can I synthesize these perspectives? How can I structure reality so that contradictions feed into integrated solutions? How can I compromise? But more importantly, they prioritize questioning answers over answering questions. They stop choosing between binary options and instead combine the best parts of both. They move past short-term problem-solving and into long-term system-building.

Where Advocates may burn themselves out supporting others, Architects conserve their energy by designing structures, whether social, personal, intellectual, anything really, that do the supporting for them. They know that a well-crafted system can sustain growth more reliably than any one person’s heroic effort.

But the Architect’s strength is also a challenge: systems can become rigid. There is a temptation to overdesign, to seek order where chaos is necessary, or to prioritize the framework over the people it was meant to serve. Architects must constantly balance the elegance of their systems with the messiness of lived reality. Unfortunately, happiness itself cannot be systematized. See Between Storms and Structures in Cognition and/or Can You Outsmart Happiness? in Intrapersonal Tensions for more details.

The only way forward is through Maximization: optimizing every part of the integrated system, knowing when to move beyond the system, and pushing life toward its fullest potential. Architects must eventually look beyond structure and ask: How can I get the most out of each piece? How can I live more fully, not just design more fully? This leap takes them into the Sage rank, where wisdom shifts from construction to lived experience.

Tier IV: Maximal Living

The final tier is not about control, rebellion, empathy, or even structure. It is about living as much as possible, beyond ego itself, sometimes beyond systems, and usually beyond language.

Sage

Sages want to maximize and come to peace with as much of existence as they can while retaining their understanding from the previous levels, primarily Architect. They see the world largley for what it is and hold lightly to essentially everything.

The Sage represents the culmination of this framework. Able to integrate multiple valid perspectives and able to design and build systematic structures for living, the Sage now seeks to maximize the human experience.

This does not mean chasing constant pleasure or achievements. Instead, it means recognizing when systems serve you and when they should be set aside. Sages know how to live fully in all circumstances: learning, enjoying, and experiencing without clinging to anything, really. They embrace humility, growth, and wonder.

Sages live with a lightness that comes only after deep struggle. Though they often appear naive, they are anything but. Having passed through all of the previous levels of development, they know life’s complexity better than anyone. But they no longer feel the need to dominate it or even explain it fully, since they also recognize that individuals require different kinds of maximization based on their rank and perspective. They can participate in life without fear, forgive without bitterness, and let go without regret. They are as close as humanly possible to peace without apathy.

This makes them profoundly adaptive. Where Architects seek to refine systems, Sages know when to bend or even discard them. They can find joy in simplicity and meaning in failure. They are comfortable with paradoxes and uncertainties, because their wisdom tells them that life is sometimes not about resolution, but about experience.

While the Architect might swear by the words of the Codex or something similar, the Sage understands when to think beyond the categorizations of the Metacognitive Framework and the ideas of the Codex. They are both systems, and although useful, are still approximations and do not apply in all contexts. No map can ever substitute reality, and the Sage understands this, while still using maps in their proper domain.

Anything beyond this rank becomes too fuzzy to describe because wisdom transcends language itself. For all practical purposes, reaching Sage is the goal. It represents fulfillment, happiness, and meaning at their deepest levels. It is not the end of the journey, but the state in which the journey itself becomes the destination.

Interactions

Individuals live, work, and clash with others across all tiers. The way ranks interact reflects their orientation. Below is a simplified map of how each rank tends to engage with others. You should recognize having or seeing some of these interactions at some point in your life.

| From Row to Column | Participant | Outlaw | Pilot | Advocate | Architect | Sage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Mutual comfort in shared systems. | Fears and condemns Outlaws as disruptive. | Admires Pilots but feels intimidated. | Trusts Advocates deeply, seeing them as protectors. | Struggles to understand Architects’ frameworks. | Views Sages with awe, but often cannot truly comprehend their abstractness. |

| Outlaw | Sees Participants as naive sheep. | Rivalry for dominance. | Respects Pilots’ agency, but envies their discipline. | Distrusts Advocates as manipulative or patronizing. | Challenges Architects, often rejecting their systems. | Shrugs at Sages, unable to grasp detachment. |

| Pilot | Work with Participants but focus on themselves. | Sees Outlaws as what they “could have been.” | Competitive but respectful of other Pilots. | Skeptical of Advocates, accusing them of weakness. | Fascinated by Architects, though wary of losing agency. | Struggles to grasp the Sage’s freedom from ego. |

| Advocate | Protects Participants, often at their own expense. | Tries to “redeem” Outlaws, often failing. | Pushes Pilots to care beyond themselves. | Collaborative but prone to burnout and enabling. | Both admires and resists Architects’ systemic practicality. | Reveres Sages as living ideals of compassion. |

| Architect | Designs systems to utilize and elevate Participants. | Attempts to restructure Outlaws but rarely succeeds. | Offers Pilots perspective, sometimes provoking resentment. | Grounds Advocates, encouraging them towards integrated structure. | Engages other Architects as peers in synthesis. | Recognizes Sages as the natural end of their path or attempt to systematically retain control. |

| Sage | Sees Participants with compassion, neither pity nor scorn. | Accepts Outlaws without judgment, but does not enable them. | Encourages Pilots to loosen but not release their grip on control. | Affirms Advocates’ compassion while leading them towards integration. | Releases Architects from over-structuring, teaching when to let go. | Other Sages are simply companions in fullness of life. |

Transition and Stagnation

Growth within the Metacognitive Framework is never without consequence or without risk. Each movement demands something of the individual: a surrender, a sacrifice, or the letting go of a former certainty. At the same time, refusal to move forward, clinging too tightly to a single mode of thought, risks stagnation or regression. Both factors define the shape of the snake: each step of growth leaves a husk behind, and each refusal to move leaves one trapped in a skin too small to contain them.

Transition

Every transition in this framework has a cost. To rise into a new rank means leaving something behind, and the greater the leap, the greater the surrender.

- Participant → Outlaw: The cost is security. To leave behind the comfort of playing along, one must abandon the illusion that belonging is guaranteed. What was once safe now feels suffocating.

- Participant → Pilot : The cost is trust. Betrayal shatters the belief that the world is fair or that rules will protect you. This transition feels violent because it is, the world rips away its mask, and you must now fend for yourself.

- Participant → Advocate: The cost is naivety. To grow through empathy, you must surrender the simplicity of blind following and confront the complexity of multiple perspectives.

- Outlaw → Pilot: The cost is pride. Outlaws cling to control of the external world, Pilots take ownership of the internal. This requires humility: admitting that you, not the world, are the problem.

- Pilot → Advocate: The cost is ego. Pilots must admit that their pain does not define all of existence, and that others’ intentions, though flawed, are often genuine. To forgive is to release the shield of defensiveness.

- Advocate → Architect: The cost is certainty. Advocates thrive on championing others, but integration forces them to admit that no single virtue suffices. To systematize is to dissolve the illusion of any absolutes, including moral.

- Architect → Sage: The cost is attachment. Architects must release their grip on not only systems and structures, recognizing that no framework can capture life in its entirety, but also the external world in general. Detachment allows the Sage to live fully without clinging to control.

Growth is not necessarily additive. You do not simply gain new skills or insights, you surrender pieces of yourself in order to become something greater.

Stagnation

Just as there are costs to growth, there are consequences to refusing it. To linger too long in one rank is to risk corruption of its virtues into their lesser forms. Each rank contains a trap, a way in which its natural mode of cognition, if left unchecked, folds in on itself.

- Participant Stagnation: Comfort becomes conformity. Participants who never grow may lose individuality altogether, becoming little more than extensions of the systems around them. Insecurity makes them cling harder to rules, defining meaning by obedience.

- Outlaw Stagnation: Rebellion hardens into bitterness. Outlaws who never mature into Pilots often collapse into narcissism or nihilism, resenting a world they cannot control yet simultaneously refusing to take control of themselves.

- Pilot Stagnation: Agency rots into tyranny. Pilots who cling to self-prioritization can become dictators of their own lives, endlessly improving and conquering yet never forgiving. Their strength ultimately becomes a cage.

- Advocate Stagnation: Empathy becomes indulgence. Advocates who cannot integrate perspectives often enable weakness in others, mistaking comfort for growth and sympathy for salvation. They martyr themselves to causes that no longer truly help anyone.

- Architect Stagnation: Structure calcifies into rigidity. Architects who fall in love with their frameworks risk suffocating within them, confusing complexity with truth and the map for the territory.

- Sage Stagnation: Even here, stagnation lurks. Detachment may turn into apathy. What was once freedom from ego may collapse into refusal to engage with reality at all.

Regression is also possible, although not applied in the traditional sense since you occupy several ranks at once. A Pilot who cannot forgive may unconsciously slide back into Outlaw bitterness. An Advocate drained of energy may collapse back into Participant passivity. The snake does not move only forward, it coils, recoils, and sometimes retreats.

Growth, then, is not a linear path, but a process of cautious negotiations. Each transition asks for sacrifice and each delay risks decay. To live metacognitively is to accept that learning itself, though costly, imperfect, painful, and never complete, is the only true safeguard against stagnation.

Conclusion

The Metacognitive Framework is not a ladder, but a river. You move through its ranks like a snake, weaving across paths of pain, virtue, and wisdom. Some stay Participants, others drift into Outlaw, some grow into Pilots, others advocate as Advocates, and a few rise to the systematic clarity of Architects and the life-embracing wisdom of Sages.

Each transition demands something of you: to suffer, to take responsibility, to understand, to forgive, to integrate, to maximize. The framework is not about judgment, but about recognition: seeing where you are, where you’ve been, and where you might go next.

In addition, this framework should make sense when applied internally, but be cautious when applying externally. What this means is that you might clearly see your own path, but you can’t see exactly where others are coming from or exactly what they’re growing into, at least not in full, because of the nature of consciousness itself. Read Between Mirrors in the Interpersonal Tensions section for more details.

As an example, you might view somebody as a Pilot, while from their perspective, they are an Architect who just so happens to appear as a Pilot in personality and/or behavior. Or you see someone as a Participant when in reality they are a Sage. Or they appear as an Advocate but are actually a slightly outspoken Participant. And they might occassionally act in a manner that shatters your illusion. Others can only be judged through their external manifestations while this framework emphasizes internal intention and understanding. Thus, it is difficult to place others on this framework.

In the end, cognition is primarily about three separate things: 1) thinking, 2) thinking about thinking, and 3) simply living. The further you move through the framework, the more life becomes not something endured or resisted, but something embraced, understood, and enjoyed, despite its difficulty.