Cognition

Knowledge

The acquisition of knowledge is a deliberate, strategic act. It is the process by which a person sharpens their perception, extends their agency, and expands their influence over both internal and external conditions. Knowledge is not simply a collection of facts or concepts, but a multiplier: a resource that transforms what one can do, what one can anticipate, and what one can resist. The person with knowledge moves through the world differently because they see it for what it is, not what it appears to be.

It is neither idealistic nor illogical to claim that knowledge is power. It is power in the most literal, mechanical sense: it enhances the capacity to shape outcomes. Those who acquire knowledge with intention secure for themselves advantages unavailable to those content with inherited assumptions or superficial awareness.

Acquisition

Knowledge begins with exposure, but is truly forged through filtration. Most people confuse information with knowledge, failing to distinguish between raw data and actionable understanding. Information is everywhere: in conversations, books, environments, behavior. But until it is contextualized, interrogated, and connected to what is already known, it remains powerless.

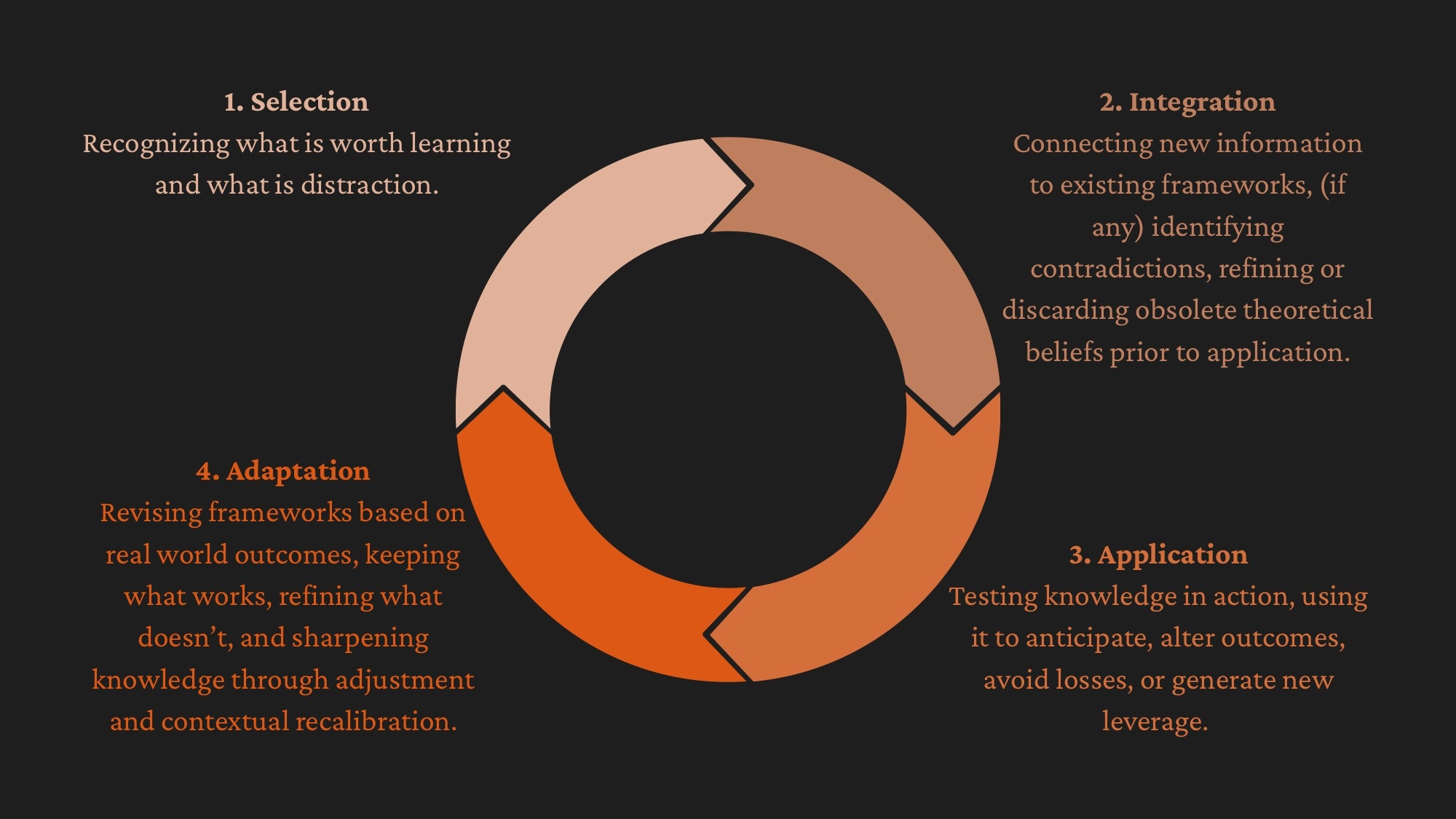

Acquisition, properly executed, involves four steps:

This process is recursive and no steps can be skipped. It requires both theoretical understanding and practical application. Every new piece of knowledge modifies the filter through which future information is judged. The more you know, the sharper your selection process becomes. The novice absorbs as much as they can, while the veteran discards ninety percent of what crosses their path, honing in on what disrupts, confirms, or strategically enhances their understanding.

The acquisition of knowledge is not a phase. It is a permanent and repeating process of a competent life.

Abilities

Pattern Recognition

The first and most immediate ability knowledge creates is pattern recognition: the capacity to notice recurring structures, causal relationships, and embedded incentives within complex systems. The ignorant see events as isolated incidents. The informed see them as inevitable results of conditions and choices.

A historian does not merely know facts about past events, they see history repeating itself in patterns within present behavior. A strategist does not merely understand human nature, they map its strengths and weaknesses and use them to predict or shape outcomes. A person who studies their own emotional tendencies recognizes when their instincts are about to lead them off course.

Pattern recognition converts a chaotic, overwhelming world into a network of interconnected probabilities and tendencies. It grants a person the ability to predict, not with certainty, but with increasing accuracy, which in practical terms is all that really matters.

Vision

The second ability is option expansion: the widening of available responses in any given scenario. Knowledge prevents a person from being trapped in binary thinking, in false dilemmas, in reactive stances. It reveals alternative routes where others see dead ends.

A tactician who understands the process of negotiation possesses more than the standard options of aggression or submission. They perceive delay, redirection, misdirection, and incentive structuring. A person who studies markets recognizes when the masses are driven by emotion and when opportunity exists by exploiting it. A self aware individual sees the choice not only between indulgence and abstinence, but between strategic indulgence, temporary abstaining, and redirection of desire.

In any situation, knowledge increases the number of viable moves. And in an uncertain world, he who has more options available survives longer, suffers fewer losses, and exploits more openings.

Foresight

Another ability is anticipatory defense: the capacity to identify emerging threats before they materialize. This requires understanding how systems fail, how people deceive, and how incentives warp outcomes over time.

The person ignorant of these patterns is reactive, constantly surprised by betrayals, market downturns, personal crises, or ideological shifts. The person with knowledge observes the precursors and makes adjustments long before others notice. They see the cracks in alliances, the overextension of resources, the misalignment of incentives.

This ability is not paranoia. It is predictive vigilance. It allows for controlled risk taking, for placing oneself where the probabilities favor them in the long term. In both social and practical terms, it reduces the incidence of losses, from minor to catastrophic.

Selectivity

Knowledge refines judgment. The uninformed evaluate options based on impulse, appearance, or sentiment. The informed evaluate based on structure, precedent, and consequence.

This difference determines who wastes years on doomed pursuits, who invests resources into unwinnable conflicts, and who repeatedly mistakes temporary excitement for solid opportunity. Knowledge enables a person to distinguish between signal and noise, between essential risk and meaningless hazard.

A discerning person wastes less time, energy, and social capital. They place their bets where outcomes matter and probabilities favor them. They do not chase every opportunity, they pursue selectively, and that selectivity is what makes them effective.

Adaptation

Finally, knowledge grants disciplined adaptation: the ability to adjust beliefs, strategies, and behaviors as new information reveals itself. Most people cling to outdated knowledge because it grants psychological comfort. The intelligent discard it because it impairs function.

This requires not only awareness of new facts but also recognition of when old frameworks no longer serve their purpose. The ability to pivot without loss of identity, without collapse into nihilism or blind conformity, separates those who merely accumulate knowledge from those who wield it effectively.

Adaptation does not mean abandoning principles. It means updating tactics, recognizing when conditions shift, and avoiding the fatal rigidity that has toppled every empire, institution, and ideology that mistook temporary success for eternal victory.

Hierarchy

Not all knowledge is equally valuable. Practicality matters, especially so in this context. Theoretical knowledge has its place, but practical application is what must be prioritized. Reality is complex, changing, and rarely aligns cleanly with theory. Without real world engagement, there is no way to accurately predict how theory will actually perform. Application determines practicality by forcing confrontation with consequence and interconnectedness.

Note that the Codex is all technically theoretical knowledge from the perspective of the reader. Obviously, I have pulled from my own experience, but still: the Codex means nothing if you do not actually apply any of its content within your life.

The knowledge hierarchy is as follows:

- Survival knowledge: What keeps you alive, out of avoidable danger, and functionally independent.

- Strategic knowledge: What increases your ability to navigate institutions, systems, people, and the world you are in at large.

- Self knowledge: What helps you keep yourself in check and consistently growing, what matters to you, and what helps you thrive.

- Supplementary knowledge: What refines your craft, deepens your analytical capability, and expands your abilities.

A competent person seeks first what is necessary, then what is advantageous, then what is vanity.

Notice that while the forms of knowledge discussed in this entry span multiple tiers, what most people imagine when they think of knowledge typically belongs to the “Supplementary” tier, the least important in the hierarchy. This is because we tend to glorify specialized or abstract knowledge while neglecting the foundational abilities required to utilize it. It doesn’t matter how complex or well designed your ship is if you don’t know how to navigate with it. You need a solid foundation in staying alive, operating in the modern world, and understanding yourself at least well enough to make proper use of any other form of knowledge. This is why the Codex discusses strategic and self knowledge in extreme detail. A person with a small, simple ship is still going somewhere. A person surrounded by knobs and dials they don’t understand is going to sink.

Eternal Scholar

No matter how much is learned, complete mastery is never truly reached. The acquisition of knowledge reveals not only new abilities, but also emerging ignorance. Every system, skill, or theory, when understood deeply, exposes its own limitations, exceptions, and contradictions. This is an inherent feature of a complex reality.

The illusion of having “arrived” is one of the most dangerous myths an intelligent person can adopt. Those who believe they have nothing left to learn stagnate, become rigid, and gradually develop a disconnect from reality. Even foundational knowledge can degrade as conditions shift. Because, one way or another, ideas evolve. Contexts change. And what was once sufficient understanding must be revisited, not because it was wrong, but because the world is not static.

The competent person remains a permanent student, an active interrogator of patterns, assumptions, and emerging variables. They recognize that the more they know, the more precise their awareness of what remains unknown becomes. The ability to recognize one’s ignorance is a humility that prevents complacency, sharpens observation, and maintains the intellectual flexibility required to pivot when yesterday’s certainties collapse.

The pursuit of knowledge is a mountain without a summit. You learn to climb not to reach a final destination, but because the alternative is always either stagnation or regression.

Mechanisms

The acquisition of knowledge is not a virtue in itself. It is a tool, a multiplier of power, and a mechanism for agency. Its worth is measured not in how much one knows, but in how effectively that knowledge translates into superior perception, decision making, and control.

The person who understands without applying builds a library in a collapsing house. The person who applies without understanding creates a tool they don’t know how to use. But even these are lesser failures compared to those who acquire knowledge without discipline, strategy, or purpose.

In a world governed by complexity, scarcity, and conflict, knowledge is functional power: an ability that multiplies agency, expands options, and anticipates what others miss. True competence demands not just knowing and doing, but acquiring and wielding knowledge with precision and intent.

Knowledge is not optional. It is what separates the player from the played.